Is consent a panacea for online danger?

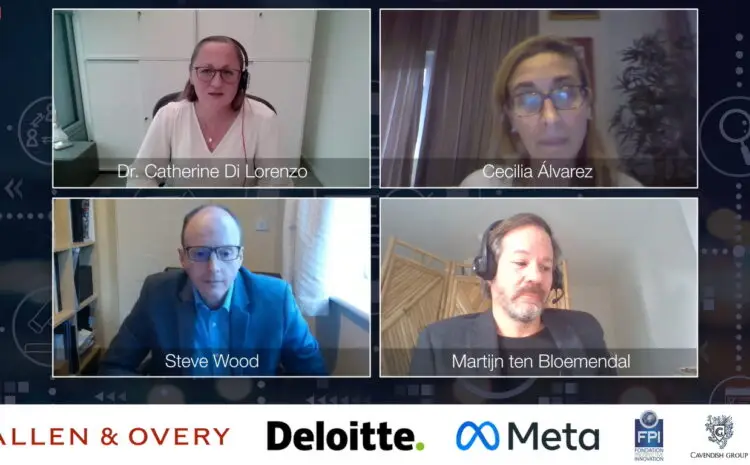

Does consent offer the best privacy and safety for internet users? And what are the issues around consent as a legal basis when it comes to children? Steve Wood, Consultant, Allen & Overy, Cecilia Álvarez, Director of Privacy Policy Engagement, EMEA, Meta and Martijn ten Bloemendal, Global Privacy Counsel, AbbVie dived deep into the subject at RAID in October. Here we share part of the discussion, moderated by Catherine Di Lorenzo, Partner, Allen & Overy

Catherine Di Lorenzo, Partner, Allen & Overy: Steve, as an ex-regulator (former Deputy Information Commissioner at the UK Information Commissioner’s Office), how do you think valid consent of children should be collected?

Steve Wood, Consultant, Allen & Overy: The key message is not to assume that consent is always needed when you’re processing personal data of children. It depends on the context and the relationship. It can be very different, for example, when a child is using a commercial service online or it’s a scenario related to their interaction with education or health or other organisations.

The other key message is that consent is not a silver bullet or a magic solution in terms of protecting children online. Though of course we need to think about when it is appropriate to have a standard of consent.

So if a child is under a certain age – in certain countries in the EU that is under the age of 13, in other countries it’s the age of 16, so the GDPR doesn’t set one standard – if you are relying on consent as the legal basis for a child using an information society service and they’re under one of those ages, then you have to use parental consent. If the child is over the age, then you can obviously seek consent from the child themselves.

So it’s really important that services are designed with those key interactions in mind, and understanding how they can work on a practical basis. It’s about understanding the parent-child relationship, how you can do that in a practical and sensible way, and what is a proportionate way of verifying parental consent using privacy-by-design to make sure you’re not collecting more data and making the process more intrusive to do that.

How we can we undertake more research about these issues? And how can we learn from the different solutions that companies are deploying at the moment? How can we make consent work in practice is going to be really important.

Catherine Di Lorenzo: Cecilia, what’s your view on child consent and how to collect it?

Cecilia Álvarez, Director of Privacy Policy Engagement, EMEA, Meta: There are two main issues. The first one is with respect to age assurance. I think we need a risk-based approach, because there is always a trade-off to be made between, on the one hand, youth empowerment/autonomy in the exercise of fundamental rights – privacy included, but others as well – and, on the other hand, youth protection, as well as the parents’ role in this connection. So it’s not only an interaction between a services provider and the user – but an issue where different stakeholders should play a role.

Focusing on age assurance, let us think about the use of IDs which are seen by some, apparently, as a kind of golden standard. However, we must consider that most teens do not have IDs to start with; we cannot forget that IDs can also be falsified, and IDs provide additional information (about the children, their parents, address, etc.) that is not necessarily relevant for age assessment. We need to look beyond. Other available means might be personal-data intensive to be effective, for example, in their training (based on AI models) rather than in their operation.

The second issue to address is parental consent. Let’s imagine that we have been successful in assuring the age of a user. Depending on the age threshold (as determined by local law), we then need to assess whether parental consent is required: this is not an automatic decision; indeed, we need to assess whether the legal basis for the relevant processing purpose is consent and, only then, whether parents should grant such consent on behalf of their child. If consent is the route to follow and if it shall be a parental one, imagine how difficult it is to ensure that a person is actually the parent of the minor at hand, and whether this person is actually legitimised to take alone the relevant decisions without the children’s say, without the other parent’s consent, or maybe without the state intervention. Can we really expect services providers to become Family Law experts in all jurisdictions, to request and become experts in assessing divorce rulings, adoption rulings? We must really think about how all of this might work in practice.

And we must factor the conversations that we need to have, as parents, with our children in this context (i.e., when granting or not a consent on behalf of our children). I am not talking here of very young children, such as those of eight years old or seven years old. Indeed, there is a moment in which it is desirable that parents-teens discussions are happening, because any teen or young generation wants to grow and needs to have a gradual autonomy. We need to find a balance, as parents, regarding how much we leave them to experience alone or and which is the level of protection we consider appropriate. And to find this balance requires family conversations, since parents are those who really know their children’s needs (hopefully) and parents have their own education goals. Service providers should not and cannot replace parents from this point of view. They can, however, facilitate that that these conversations take place, among others, through education materials and parental supervision tools.

Catherine Di Lorenzo: Martin, if you had a chance to tell the regulator something you need from them in order to make your life easier when it comes to the collection of consent in general or child consent in particular what would it be?

Martijn ten Bloemendal, Global Privacy Counsel, AbbVie: On consent in general I would say, with regard to research, to steer away from focusing on the consent in documentation, in conversation and what have you, because especially in the health space there’s a lot of legacy developments and there you see again this focus on consent. And I think we are not thinking about the downline ramifications of it. if you want in Europe for example to be in innovative with data, you want to use data in innovative ways that we might not have thought of before, we cannot say that in every case that we come up with something new we ought to get consent. And actually the GDPR has many specific derogations that say on a decent circumstance you don’t need to get consent.

But nonetheless you see a repeat of this idea that consent is the gold standard and I think it makes intuitive sense, but it can have downstream affects that are not per se imagined especially as it relates to data and research.

I’m not going to say that data is a new gold or attitudes like that, but obviously data is extremely important, and innovative ways of analysing data for economic development. So we have to be very cautious if we constrain that development purely because we believe consent is the gold standard and that is the be all and end all.

To listen to the full panel Deep Dive: Consent as a Legal Basis, which also explores contract as an alternative basis, go to https://www.raid.tech/raid-h2-2022-recordings